Your house

You get up earlier than usual, at dawn; the suburb is hushed. You pad quietly downstairs, brew a coffee and settle into a soft chair for half an hour of calm. This is your time: even the dog is still asleep. Maybe you’ll read a long essay from The New Yorker. Perhaps do a little writing. Maybe you’ll go outside before making the kids’ lunches and listen to the birds.

By 7am you’ve done none of this. But you have watched a sloth getting rescued from a highway, and a video of two moles fighting.

Your street

You wheel the council recycling bin from the carport to the path outside your house. You swing the bagged rubbish beside it and leave it carefully on the kerbside with the knots usefully facing up.

Your home is at the midpoint of your street. You glance left and right at all your neighbours’ bins, sitting at intervals as far as the eye can reach, to the eastern and western vanishing points of Parkvale and Hatton Street. This long view, this quiet time, makes you remember Anzac Day morning five years ago, when everyone was confined to their households but encouraged to stand on the streets despite this, to acknowledge the usual dawn service.

Exactly like this still, April morning, you and your husband went outside and stood awkwardly at this kerb. He switched on the radio and you each took an earpiece. Then your opposite neighbour and her family emerged, thoughtfully setting up a speaker so the service was audible among the neighbouring houses. The announcer’s reverent tones rippled gently along the street.

The elderly couple next door to them emerged in their dressing gowns and stood uncertainly together on their step. Your neighbours to the left stepped outside as well. A jogger - to be honest, he looked like an executive logging steps - pounded along the middle of the deserted road and had the integrity, at least, to look ashamed of himself.

Then someone three or four houses away stood unseen in their garden and played The Last Post on a bugle. The mournful notes dissolved into the air. It was as if they had never been, and we had only imagined them.

We all went back into our houses and returned to our unseen lives.

Cable Street

A pair of trainers, toddler-sized, have been left neatly on top of a parking meter by whoever found them. It’s common to see a single lost mitten hanging from a fence or a baby sock in the gutter, but a smart pair of tiny trainers? Were they kicked off in fury, or thrown, slyly, from a moving car?

You almost admire the kid.

Circa Theatre

There’s time before your meeting, so you slip upstairs and wander around. You find a staircase leading up, seemingly to nowhere. You follow it, and it finishes at a tiny doorway which opens to the roof.

You take other blind turns. A dark little room full of electrical equipment - the lighting nerve centre for Circa One. A rehearsal room you’ve never seen before. A keyboard is propped casually against a wall. The masonry facade is exposed here; girders tie this old brickwork to the rest of the building.

You look out of a dusty, Georgian-style window across to the nineties hulk of Te Papa. The old facing the new. A rough sleeper trundles a shopping trolley between the two buildings, his possessions bundled inside it. It doesn’t seem fair that as well as every other challenge he’s facing, he doesn’t even get the dignity of personal privacy. Everyone can see what little he has.

You notice an electric kettle among his bundle, and you can’t get this out of your head.

Rehearsal

You sit on a hard chair between the director and the producer to watch a rough run of the entire show. There are two weeks left before curtain-up. A circle is taped on the floor; this is the stage.

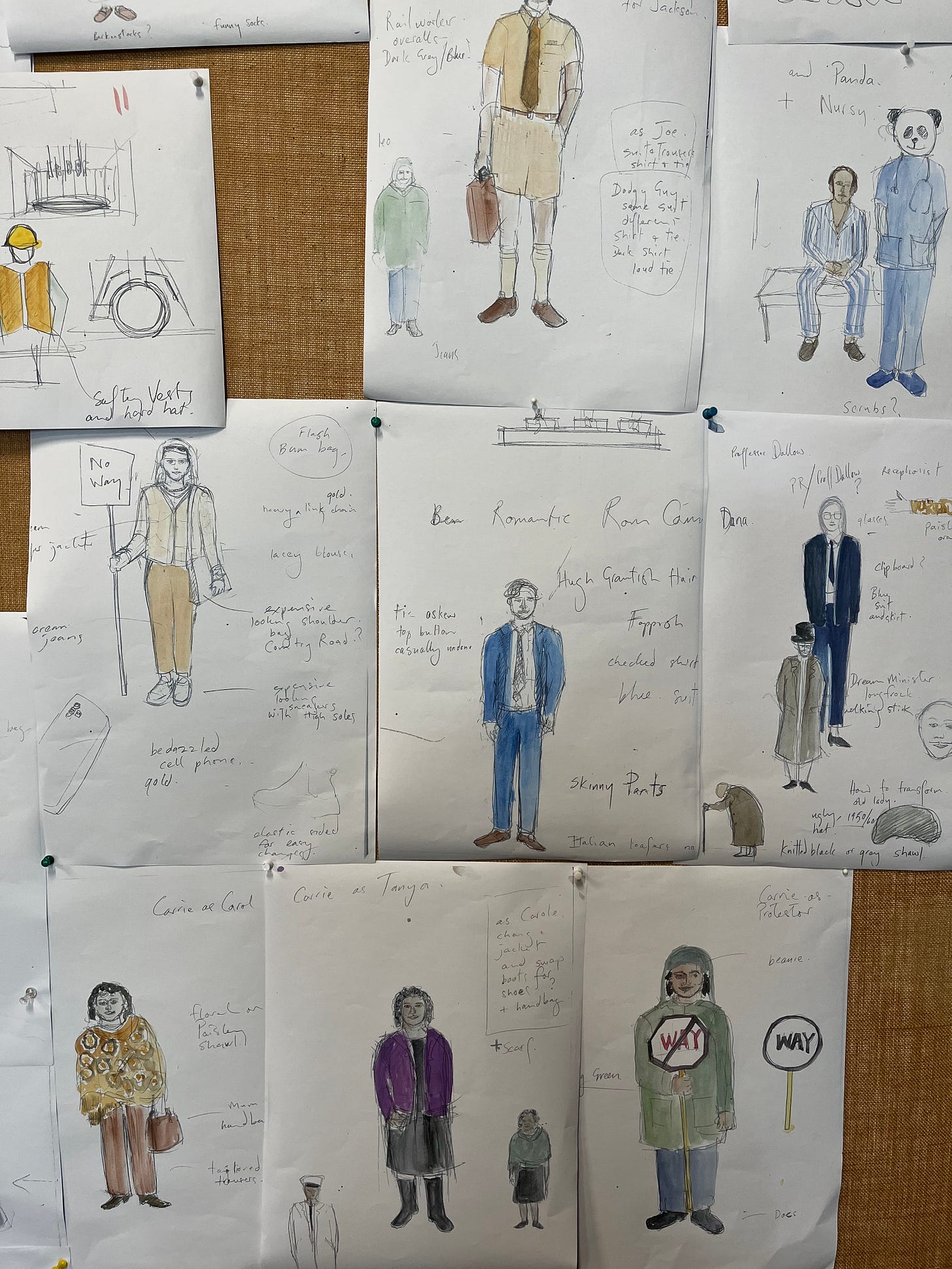

There are cubbies full of props (an adding machine; the head of a costume bear), a hanging rack of jackets and a pinboard, papered over with costume designs.

The run begins and the people you know as Lily or Alex or Bron become other people entirely - Sophie and Randall and Nic. They sing, they whizz across the floor on wheeled chairs, they change accents or hats, they march, crash to the floor, argue, clink glasses, hallucinate, dream out loud, pause for laughter. They ask, quickly of the director, “Line?” if they run out of words, which is hardly ever. Sometimes they stare fixedly at you, but they’re not actually seeing you. You can’t believe you’re really experiencing this, the assembling of a show from the ground up.

At the end, your eyes sting from laughing. You have to wipe them several times. Carrie just has funny bones; you could watch her do anything. Jackson crackles with electricity. Lily is just 21 and she wears her lead role so lightly. How does Bronny do so many accents, and how does Alex - so quiet in the Green Room, so unassuming - shapeshift into someone so confident, charismatic, loose-limbed? You’re suddenly shy around them.

You skitter down the back stairs and leave the theatre by the code-entry rear door. Like an ACTOR.

Bowen Street

You flick on RNZ National. You’re not listening as much as you once did. You used to work there; you have friends there; sometimes you actually go there, clamp on headphones in a studio, and review books. Radio helped educate and inform you. You’ve been listening, greedily, since you were 18.

You blame your diminishing attention span. You blame that you’ve been listening for so long now that every interview now sounds familiar, like you’ve listened before. You blame the fact Kim Hill left. (Nobody you know has accepted that Kim Hill has left.) You blame your own brain fog; listening to an intense conversation while driving unpredictable Wellington streets (Cargo bikes! Road cones!) asks too much of you.

“And now, the dung beetle,” says the announcer.

You turn it off.

Karori Road

You drive past a cyclist with a misshapen backpack. He pulls up beside you at the Marsden Village shops and you realise a dog is stuffed inside the bag. Its nose points forward, its narrow face eager, its front paw looped around its owner’s neck. This makes it look tipsy and satisfied, as though it had too many beers at the pub.

You glance at other drivers, but nobody has noticed. Or if they have, it must seem normal to them.

The lights change and the dog streaks ahead, sailing down Karori Road.

Woolworths, Karori Mall

She says, “Breathe in through your nose, and out through your mouth,” and demonstrates.

You copy her and briefly suspend time: you feel the frazzle leave your body.

“That works,” you say.

“It’s a good trick," she agrees. You breathe performatively together. Then she asks if you want the receipt, and you say no. You lift your shopping bags off the counter.

“Thank you,” you say, but she is onto the next customer.

Your house

Your 12-year-old son saunters in the room, pleased with himself.

“Well, the last day of term ended with a bang,” he says. “There was a fight in Tech. A Year One kid licked my shoe. And, I think I have a date.”

At the doctor

You describe your symptoms and the doctor nods. She looks into your mouth and throat and informs you that you have small tonsils. You don’t know why, but this news makes you feel more feminine.

She invites you to stand on the scales.

“Can I take off my boots?” you ask; you know you’ve gained weight, but you don’t want a false reading, and your boots go all the way up to the knee.

“You can take off whatever you want,” says the doctor. What she means is, “Do anything it takes to soften the blow.”

In exchange for the knowledge you’ve gained nearly FIVE KILOS, you’re given the referral letter you asked for. Honestly? This doesn’t feel like a win.

Night, your front garden

You take the dog out to perform his evening toilet before he goes into his crate for the night. You sit in your favourite place. There are biting insects about; you’re wearing long socks to deter them. The darkness is somehow pale, and you see the blunt beaks of kaka flying overhead, cawing, and whirling their stupid donuts in the sky.

At this time outside your Mum’s, closer to the coast, honking geese would be flying over.

There is a ruru somewhere in the neighbourhood. Its call sounds like the pan pipes played soothingly in beauty salons. You breathe in through the nose, out through the mouth. This is your time.

The dog stands at the door, waiting to be let in.

Those shoes definitely fell off a car roof after being put there by a tired mum after daycare pickup. Speaking from experience.

Beautifully written Leah - at times an expose, at others an love song. Change the street names, and the birds, and we could be anywhere in New Zealand