There’s a Pūkeko in the freezer at George’s school.

These are chunky birds, by the way, with a useful bit of beef on them. Good eating: you could imagine mopping up their dark, oily gravy with a soft bread roll.

Not that anyone I know has tasted Pūkeko. You need a gun licence and a permit to cull them and besides, they take ages to tenderise. “You wouldn’t bother with the legs,” a chef once told Radio New Zealand, in case anybody listening was considering it.

I don’t think it would be fair to eat them, anyway. They’re guileless, and unlike snipes or shags, appear not to mind us. Why else would they peck along the gravel edges of country roads, as 3,000 pounds of hot and squealing metal shave past them at regular intervals? Instead of sticking to the swamps and reedbeds, as wading birds should? Some have a survival instinct, breaking into a trot and diving into grass to avoid violent death, but many take picky little steps across the road instead, all the better to be bounced off the grille of an oncoming car.

They’re simple, but I love them. Their knees bend backwards, and their juveniles are fluffy. They seem to enjoy socialising, fussing around each other like ladies at a piano recital.

I found roadkill of all kinds poignant and sorrowful — the undignified splatter of a hedgehog, its insides squeezed out like cream from a bun, or the slump of a mown-down rabbit. I even feel sorry for dead possums, as destructive as they are. Rabbits are built to burrow and possums to climb; you can’t tell me they don’t feel instinctive delight as they ruin our trees and paddocks. This might make me less of a New Zealander, but I take no pleasure in a flat possum, a tyre-mark stamped across its neck. Didn’t it once know joy?

A dead Pūkeko, though. That really feels like a waste — their lifeless blue feathers ruffling on the chipseal of Mākara Road.

I bet this particular dead bird is wrapped and sanitary, intended for skinning and plucking. Its feathers will be woven with flax fibres by a skilled Māori artist, using techniques passed down by her forbears, and possibly worn as a cloak.

I expect its red bill and the white underside of its tail are hidden inside clingfilm and possibly, a layer of newspaper. But its frozen orange legs are sticking out, if George is to be believed — each foot divided into three toes, a prehistoric claw at each tip.

This Pūkeko will be treasured long into the future despite its brief, fragile existence close to the low hum of Karori. It’s a lucky bird in the long term; in the short, though, it’s stiff as a popsicle and was recently scraped off a road.

“Yep, it’s a Pūkeko,” George said gravely on the drive home from school, “and it’s definitely in there.” We passed a feral goat and then he said, “It’s next to our ice cream.”

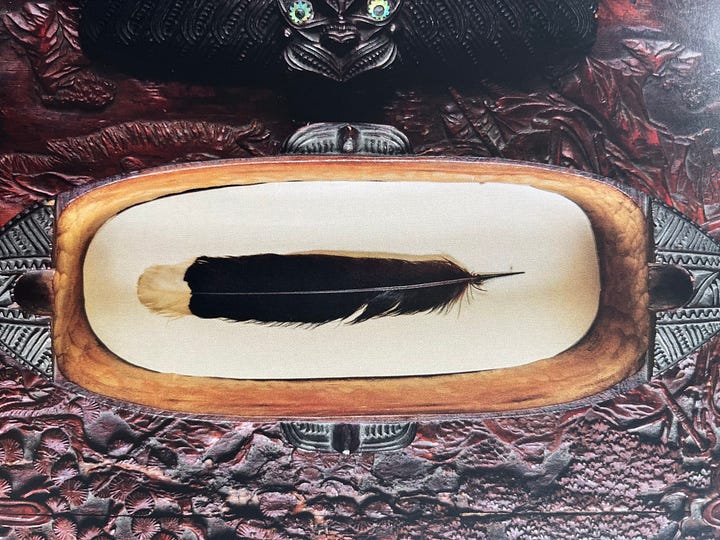

Speaking of birds, there’s a perfect Huia feather — black, tipped in white — locked in a carved wooden box, a wakahuia, in Dunedin right now. Thousands of visitors file past it each year, but nobody is allowed to touch it or look inside. Isn’t that lovely? That everyone agrees the perfect, dipped feather of a vanished bird is so precious it must be left in peace?

Sometimes, we get it so right in this country.

Mind you, somebody paid close to $50,000 for such a feather at auction last year. The auction house couldn’t reveal who, and you’ve got to hope the buyer was New Zealand based. Bidding was furious in person, over the phone and online, well over a century since the bird last was seen in the wild. Predated upon and overhunted for its feathers, the extinct Huia is still fought over and claimed by those of us less beautiful, simple, and joyful.

Sometimes, we get it so wrong.

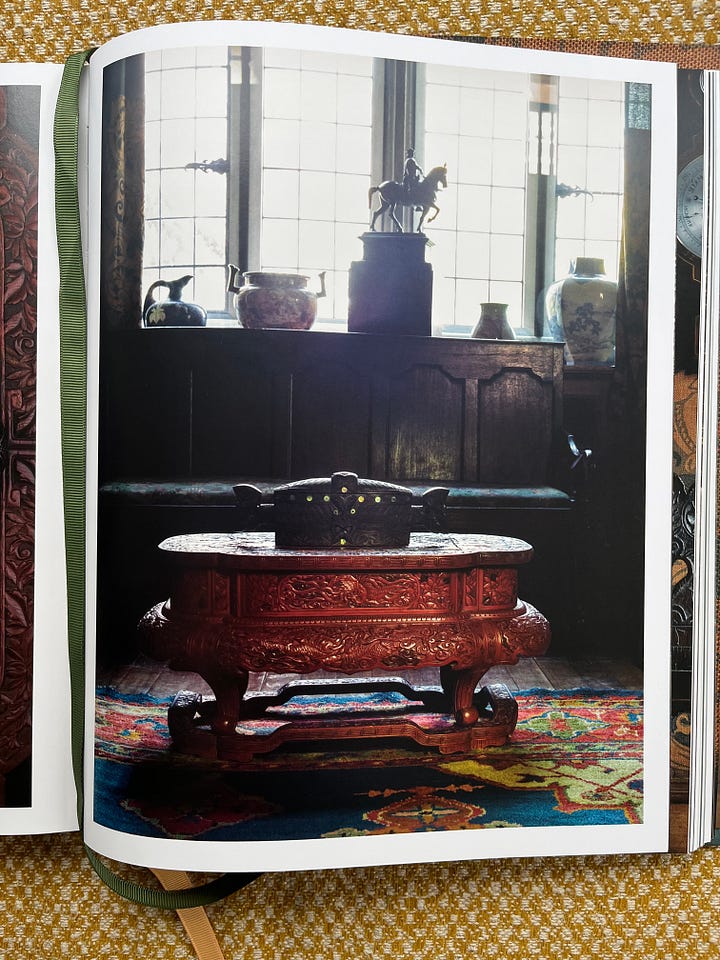

I’d forgotten about the wakahuia, though have walked past it countless times myself. It’s one of the countless treasures of Olveston, the stately Edwardian home overlooking Dunedin. As a varsity student in the early 1990s I worked as a guide there, paid $10 an hour to take groups through the house (exit your party through the gift shop, refuse any tips).

I was young and despite enjoying the job, oblivious, really. Olveston had been gifted to the city in the 1960s. It was, and still is, a perfect jewel-box of art and antiques, freezing in time a way of life that seems remote and faintly ludicrous now. Every item the family owned — from the Olympic sized billiard table to the tiniest spoon — remains where the family, the Theomins, left it. But the family is like the Huia, long gone.

It was a formal, starchy life. One of servants and tingling bells in the kitchen, which glows buttermilk yellow in the northern sun; one of masculinity, especially in the games room whose ceiling could be opened to release the fug of cigars. One of sprig-legged and fussy femininity, in the drawing room. One of deliberate gloom in the Great Hall and library, to keep the sun from priceless wallcoverings and artworks. The house gleams and hums with daily activity, but as a young person, I felt there was a lifeless quality to Olveston.

I wished there was more to tell than simply the provenance and rarity of things (the Queen Anne sideboard; the antique Spanish travelling chest). I enjoyed pointing out the evocative details — the scullery window, where eggs and produce were passed inside to the maid; the kosher sinks — but there was no drama to the house, unless you counted the vestibule, which bristled with weapons and a startling statue of David, Goliath’s severed head at his feet.

There was no ghost I could talk about — nowhere an unexplainable drop in temperature, which would have added camp to my tours. No Cluedo-style murder. No suicide, like at Larnach Castle on the Otago Peninsula, whose owner had blown out his brains in the ballroom. It must be a doddle to guide at Larnach Castle.

No clandestine affairs. Olveston was built for a blameless, middle-aged couple, who slept primly in separate beds. Olveston was no Downton Abbey, and 21-year-old me found this disappointing. I wanted my life to start. I wanted sensuality, adventure, sex. I wanted to get out of Dunedin.

I’m not as impatient now as I was then. I would lead very different tours today. I’m at an age now where I care about things like lamps and could do a solid hour on the fixtures and fittings alone. If I could take one thing from the entire, gleaming pile, it would be the green silk shade above the dining room table, and perhaps the little matching shades on all the candles as well.

I’m remembering all this because I reviewed a new book for Radio NZ this week — Olveston, Portrait of a Home. My slot ran way over time as I forgot to stick to reviewing, babbling instead about my time guiding groups and buffing the wooden floors. It’s a lovely book and kicks up the dust of my past personality, as a nostalgic song or album might for other, cooler people.

Reading it made me think about who I must have been, and who I am now. Leafing through returned me to the rooms I haven’t seen for years. I notice things I’d forgotten about and didn’t value then. If I went back to Olveston now I’d go from room to room, chasing myself, looking for glimpses in the convex mirrors and polished surfaces. Now and again, I might find her, that person, but more often than not she’d have gone.

I lived at Olveston for a while, up in the attic flat. The rent was next to nothing and in exchange, you sometimes needed to stay on site from early evening until the arrival of the first morning coachload of tourists. You’d clean the toilet block, polish the hallway floors, turn off lights and lock up. You’d stare out of the mullioned windows and wonder why you didn’t have a boyfriend, and what you were going to do with your arts degree.

My friend Jane moved in after I moved out. We met at Radio One, the student station. She was a wildly popular morning host known as Jane Insane. She had a solid knowledge of independent music and a laminated cut-out of Morrisey dangling from her rear-view mirror. I hosted a Sunday magazine show and was once told off by the programme manager for playing Alanis Morrissette. I didn’t care about music, I cared about talking, and if Alanis was that bad, why did they have her music in the cart machine? Still, I was in disgrace.

Somehow Jane and I became mates and thirty-odd years later, we went to see the documentary Life in One Chord at the Cuba Lighthouse. It’s the story of Dunedin’s iconic Shayne Carter, whose music formed the soundtrack to our undergraduate lives. He and his band had long gone by the time we arrived on campus, but his legend remained.

I hoped to see plenty of archival film of 80s and 90s Dunedin, and I wasn’t disappointed. There was the student union, and the familiar doorway of the radio and newspaper offices. There, the grimy bars and grotty warehouses. There, the bleakness and beauty of a frigid southern city whose glory days seemed firmly behind it.

Everyone sitting in the cinema looked north of fifty, murmuring with occasional recognition as certain scenes appeared on screen. Several of us needed to nip out and wee mid-movie. Not me, though. I’ve been doing my pelvic floors.

“Don’t we know them?” Jane whispered to me, indicating the row of heads in front of us. There were a lot of Gen X guys in graphic T-shirts. The women wore funky clothes. We could well have gone to uni with any of them, but I was too shy to ask.

The scene I liked most was of Carter today, standing with a group of uniformed schoolgirl singers, their clear, ringing voices softening one of his rock tunes as he smiled and nodded encouragement. His snarling punk days were over, and he was seeing his old city differently. It felt like hope and offered some kind of profound comment on the passage of time.

I met Shayne once. I was in Queenstown for the local writers’ festival, and my mate Em was tasked with collecting him from the airport, ahead of his appearance. The plane arrived early, we were late, and he was nowhere to be found. It was a terrible moment, losing the festival’s star attraction like this.

Em zigzagged away and I went to Paper Plus to find our elder stateman of rock, approaching anyone wearing black leather and an air of disdain. There were a surprising number but none of them were him.

Emma found him eventually in Baggage Claim. He was standing alone with his guitar, exactly as you’d want him to be.

Other than the radio, which spiked my heart rate and melted my nerve endings, I’ve had a slow week, made up of unremarkable hours. There were moments I’ll remember, though. When the dog nosed a dandelion clock and released all the tiny seed heads. Most floated over the grasses and away, but for one or two which caught in his moustache.

And George’s troop at the end of their weekly meeting, when the Scouts — of varying heights and degrees of scruff — line up to watch the lowering of the flag. It hangs up on the hut’s far wall, blue with red stars, ignored all evening by Scouts knotting things and climbing things until one quiet minute at nine o’clock. Everyone goes quiet and becomes briefly respectful, as a Scout winches it down the wall.

This week the ceremony took place as a Scoutmaster poured water from a metal teapot onto the fire. It hissed on the logs and billowed as smoke while the flag came down. It was briefly 1945, not 2025; this fleeting moment of shared resolve, where we agreed on something larger and finer than ourselves.

I briefly left my body. Then a Scout called, “Troop dismissed.”

Such gorgeous writing. Your similes are always so original. I am in love.

A wonderful read, beautifully complementing your book review I managed to catch on RNZ during the week.