Can we talk about Chelsea Winter?

I’ve never met Chelsea Winter but, in my mind, we’re friends. I think anyone who cooks from her books, follows her socials, buys her kitchenware, reads about her in magazines and for all I know, watched the way-back season of MasterChef when she won the whole damned thing, feels the same. Matey.

I was late to the Chelsea Winter train, so I never saw her on TV and still don’t know how she sounds. But she’s familiar. She reminds me of the kind of girl we all went to high school with — pretty, blonde and slim, an early adopter of step aerobics, who laughed in a silvery sort of way which made you regret your own personality, and whose boyfriend waited outside the main gates in a Hillman Hunter, to take her to the beach.

Honestly? We wouldn’t have been friends back then, the way we are now. I would have found her basic, and she would have found me moody and plain.

I would have been wrong about her.

To this day I still don’t know what led her to the kitchen or refined her talent, but such qualifications are immaterial. At some point there just became a national acceptance of Chelsea Winter as a cultural force. You couldn’t avoid her even if you wanted to. We were all cooking her dinners and bringing her slices to the office. Your workmates would be like, yum, is this Chelsea Winter? And you’d be like, why yes, it is.

Around ten years ago, once she was comfortably established as our favourite home cook, there was a brief moral panic about Chelsea Winter. There were public arguments about whether she used too much butter in her recipes. Or too much sugar. Or was it meat?

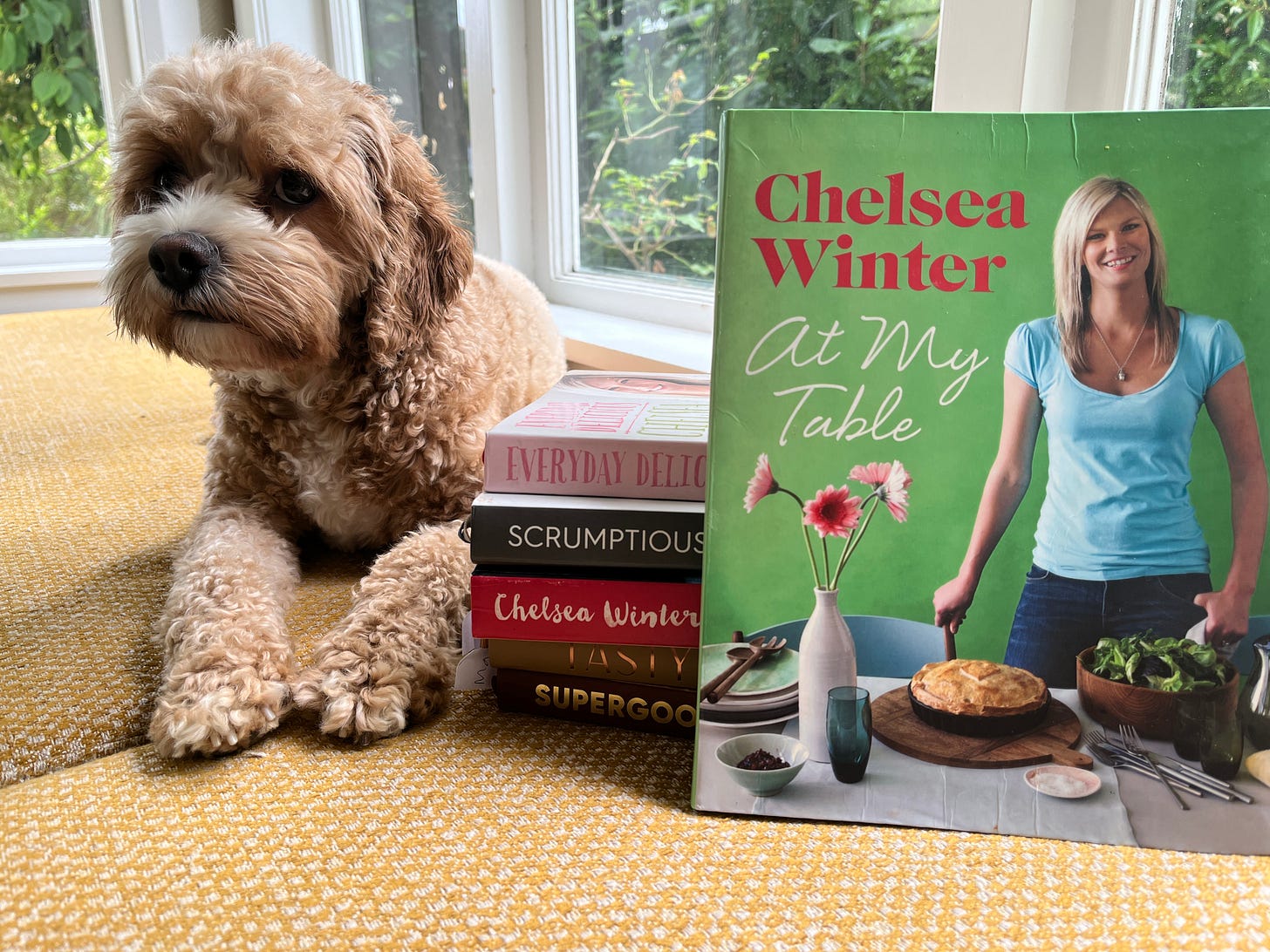

Certainly, she didn’t skimp on mince, cheese or pastry. She was a fan of flavour and heft. There were piled-high burgers in her early books and a lasagne so big, she called it The Boss. Food was carefree; eating was what you did to fuel the good times, usually with other people as good-looking as you were. Her books featured Chelsea in skinny jeans drinking wine outdoors or taking pies to the beach with her mates. The photos confirmed she was down to earth — the ultimate Kiwi compliment, meaning ordinary.

The criticism seemed unfair. To scold Chelsea, an inoffensive lover of saturated fat, was to kick a kitten. You couldn’t imagine our favourite home cook of the 1980s getting this kind of stick, but back when Alison Holst reigned supreme and went on to write entire books about mince, meal choices were simply choices. The food you ate didn’t semaphore to others your world view, social class, how educated you must be or how concerned for the environment. If you wanted mince for dinner, you had mince for dinner, washed up, and then forgot you’d had mince for dinner.

Despite the furore, Chelsea appeared unfazed. The sniping felt mealy and joyless to anyone who happened to love her Snickalicious Slice, Chelsy Con Carne and Spaghetti Chel-Fredo. The people objecting seemed up themselves — the ultimate Kiwi insult, meaning well-read and travelled.

Who cared about her critics, mooing on the radio about agave syrup? Few of us ate the way they did; they were easy to ignore.

I had nothing in common with Chelsea at this point, by the way. She was enjoying a sun-kissed sort of life far away from Wellington. Her cookbooks implied a blissful existence of summers on Great Barrier Island (fishing, barbecuing) and multi-generational family meals served on upmarket flatware. In her fourth cookbook, Scrumptious, she revealed her sexy husband, Mike, who had dark stubble, good hair and a hard stomach, upon which you could probably tenderize steak. Chelsea remarked he was away a lot for his job, which I liked to think was catwalk modelling for French fashion houses.

It’s not that I didn’t, myself, have a hot husband who was often away. I did. I just wasn’t as in control of my life as she was. My hair was fried, unlike Chelsea’s, and my meals mainly bland, unlike Chelsea’s. With two small children, dinners had to be familiar and repetitive. We were still eating at half past five, for God’s sake. Our bowls had Peter Rabbit on them. I’d probably been up three times overnight, and didn’t have the energy to make focaccia from scratch or even Chelsea’s Rozilla, which was a giant meat roll made from storebought pastry and pork mince squeezed from sausage casings.

I was too tired at that time to squeeze a sausage; just ask my husband. But I wanted to be somebody who had the energy. I wanted to be more like Chelsea and less like me. She represented the sweet spot where a person’s talent had been bearhugged by opportunity. She radiated the happiness of realized potential. As I’d no career left to speak of and only got to shower twice a week, this felt inspirational. I was rooting for her. I began to buy her cookbooks and eventually, I used them.

But by the time I bought her sixth book, Supergood, a hard rain had fallen. There’d been the Covid pandemic, for one thing. Everyone emerged slightly unhinged, strident about things that previously hadn’t mattered and arranged into angry tribes. There hadn’t been many raucous family dinners, barbecues or pie parties on the beach in 2020; we’d retreated into our homes. Growing your own food, ordering produce from independent suppliers, baking from basics, relying less on the industrial food chain, became a mainstream concern — not just for the gourmands and gourmets.

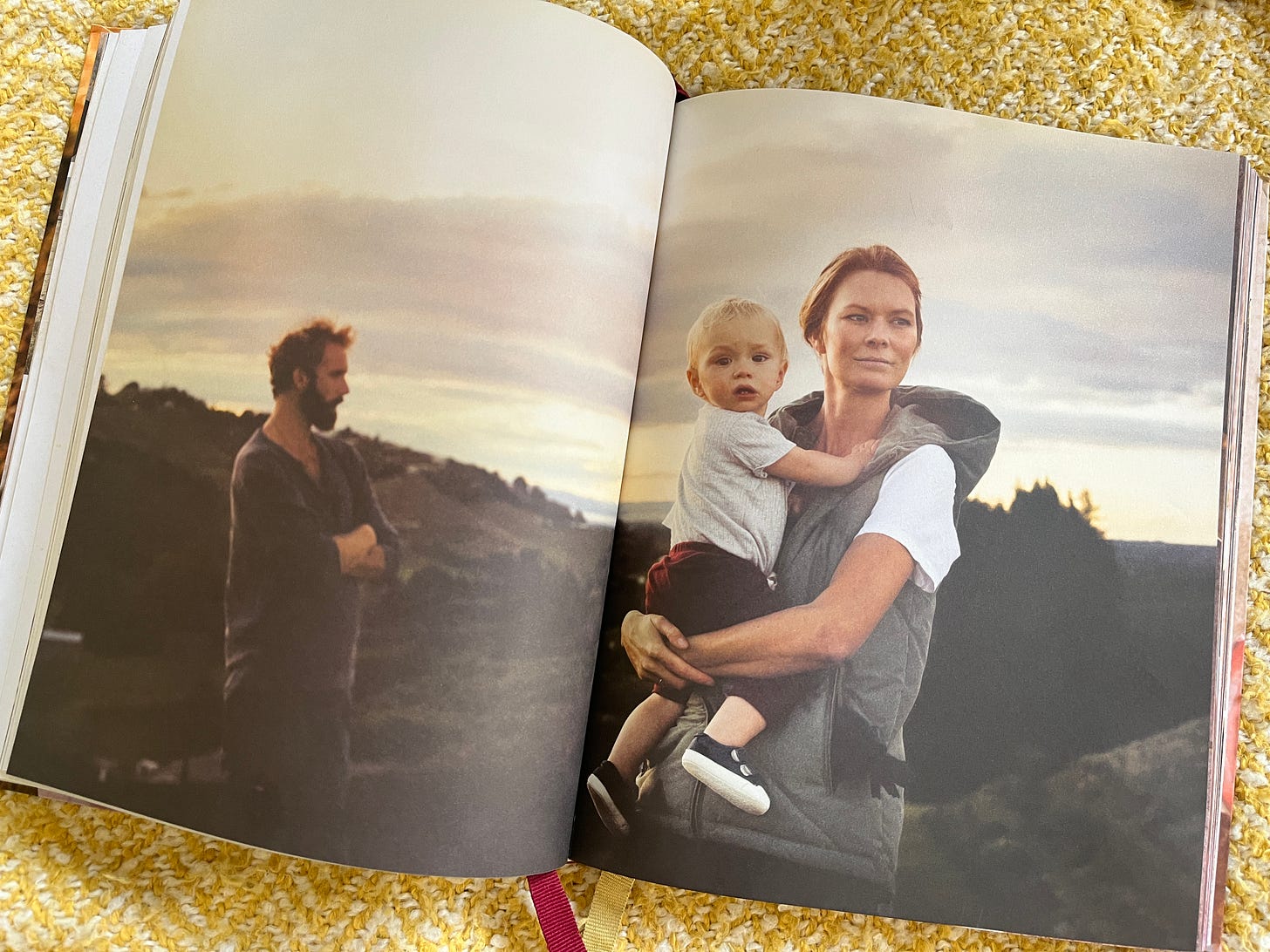

Chelsea herself, bringer of pies and sunshine, had changed too. Mike was no more; she’d moved to a lifestyle block with a serious-looking eco-spunk called Douglas, and had a baby. Supergood featured muted, earthy palettes, with photos showing Chelsea and Douglas in breathable fabrics. They seemed full of intent in the kitchen scenes, like food wasn’t just for pleasure but something to consider carefully before eating.

Having a baby turns many a parent into an evangelical food purist. I went through a phase of wanting our tots to eat like the French, with slow-cooked mains and courses for salad and cheese. I read French Children Don’t Throw Food muttering ‘Of course! Of course!’ as in a fever dream. This lasted about 18 months, at which point I gave up and handed toddler George his first Tim Tam. It was the happiest day of our lives.

But Supergood was bigger than a phase. Chelsea had done a major, un-signposted pivot. She dropped meat and dairy, and most of the gluten. She had a section called Say Hello to Your New Friends, who included cashew milk, kelp powder and chickpea brine. For many, these were unwelcome introductions. With friends like these, who needed enemies? Her boldest recipes featured tofu meatballs, lentil meatloaf and Not Dogs, which were carrots in a bun, shaped to look like franks.

Chelsea turning plant-based was like Dylan going electric. Just imagine Julia Child saying to the camera, “You know, I was wrong about cream,” and then emptying her sherry down the sink. If you were long-term fans, you’d go ape shit, wouldn’t you? And many of Chelsea’s did.

You’d think I’d have been delighted when Supergood came out. By now I was gluten-free by necessity and bored rigid by the limited foods now available. Yet I was irritated. It made me feel guilty for cooking with red meat, sugar and eggs. I was unlikely ever to open a tin of chickpeas for the water they came in; the chickpeas themselves were challenging enough. And I couldn’t forgive the fucking Not Dogs, for which I blamed Douglas.

But I couldn’t deny my relationship with food was changing. With fussy children (aren’t they all, by varying degrees?), a husband who couldn’t eat dairy, and all wheat, oats, barley and rye products strictly off limits for me, what I cooked was no longer a casual business, of flinging together casserole mix and chuck steak or swinging into a drive-thru. I had to put the effort in. I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life reading packets, avoiding cheese, and soaking beans; it seemed Totally Not Fun (like Douglas). But if I didn’t, someone in the household was going to feel sick.

I resented this, for a while, imagining everyone else enjoying their pastry, pies, mac-cheese, and baguettes. But there was no fun to be had on the cookbook shelves, either. It seems we were all saying Hello To Our New Friends - raw and unbaked ones, intermittent-fasting ones, juice cleanse and anti-inflammatory and Ketogenic ones. According to the latest science, what you ate determined how you felt and not only how long you lived. It was becoming understood you could eat yourself sick or eat yourself better — neatly pushing responsibility for their family’s health from the food industry back to the householder. Food had become a collective neurosis, and the buttery, sugary, meaty New Zealand of the 1980s seemed a distant forty years ago.

Honestly? I never cooked a thing from Supergood. Perhaps I wasn’t emotionally ready — still resentful about the foods I couldn’t eat, the endless shopping and cooking and cleaning up after cooking. But this year’s Tasty has met me where I’m at.

Chelsea and I are still way different. She’s grown her hair, and I’ve layered mine. She’s moved to the black sands and crashing surf of Taranaki, a place I grew up and couldn’t wait to escape. She is 40 now, with two tiny boys. She’s no longer with Douglas, but co-parents with him. She has “let a lot of shit go and invited a lot of magical stuff in”. This does not include refined sugar, but it’s probably the last food group left to give up. Chelsea’s found her bottom line, at last.

She’s good, mate. I mean, she’s still a bit fond of a wafty linen smock and gazing into the middle distance, but I’ve tried her Zingy Potato Salad and her Tostadas (very good) and have thought more than once about her Golden Pumpkin Pie.

She’s been a bit battered about by life, hasn’t she? And by now, so have I. In your fifties, the body you lie down with isn’t always the one you get up with. After three decades being as hard and upright as a fork, thanks to unawareness of my coeliac disease, I’m now fleshier than I’ve ever been. I swing between being okay with it - it’s natural for bodies to change in peri-menopause - and feeling low about it, unsexy, and slower to move. Nobody likes to go up a dress size.

I’ve had my share of loss and grief, as Chelsea surely has. I’ve felt alone a lot, even though there are people who love me. She’s by herself in many of her pictures, or burying her face in her children’s necks or hair. I’ve felt overcome by mothering too, in good ways and in frightening ways. She’s doing the right thing when she goes for apparently lengthy solo walks on the beach. What we both seem to understand, by now, that at the end of a day, and at the end of a life, the only one waiting for you is yourself.

It’s important to note I’ve carried out exactly no research for this piece. Like everything else I’ve ever posted, it’s a frightening glimpse into my stream of consciousness. By which I probably mean, sorry, Douglas.

Welcome to any darling new readers who’ve joined this merry band! You’ll find some good sorts here. I’m glad you came.

Can I thank those lovely readers who left me beautiful comments or emailed me privately after the piece about my late Dad? I found your messages incredibly touching and soothing, too. To be honest I was a wreck after posting it, as the impulse came out of nowhere. I wrote it in a couple of hours and hit PUBLISH, without a thought for what might come next.

I guess grief is like that. When it unexpectedly arrives, you have to invite it in, pour it a cup of tea, look it in the face. You can’t run forever, though believe me, I’ve tried.

Brilliant! I can identify with so much of what you've said here. Yes it was a shock for all of us when Chelsea turned vegan, I bought Supergood without realising but actually there are some great recipes in there which have become favourites in our household. Still love her old stuff though - her rich, creamy chicken pie is to die for! And like you I won't be trying the Not Dogs any time soon. Thanks for a very entertaining and funny piece of writing.

Interesting that Steve Braunias commented she seems always to be sad, or words to that effect. Her books sell like (ahem) hot cakes. I've never cooked her recipes. Crikey - coeliac - bummer. The upside, I suppose if there is an upside, is that at least these days bakers, restaurants, and chefs acknowledge it is real and cater for coeliacs. As ever, brilliant writing.